Beach Bums: The results are in

Regular surfers and bodyboarders are three times more likely to have antibiotic resistant E. coli in their guts than non-surfers, the Beach Bums study has revealed.

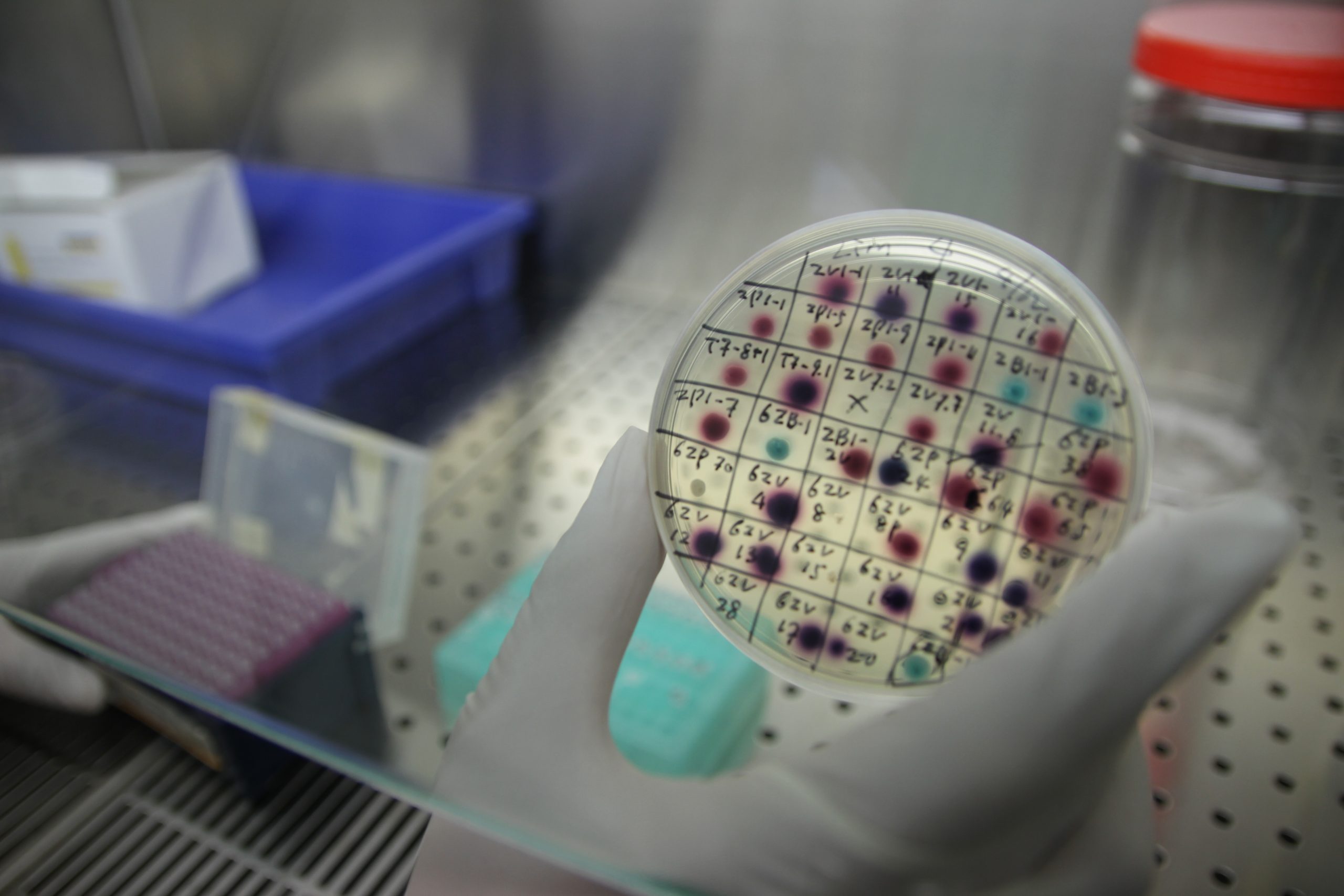

Surfers Against Sewage assisted in research conducted by the University of Exeter, to recruit surfers and non-surfers for the Beach Bums study. 300 people, half of whom regularly surf the UK’s coastline, were recruited to take rectal swabs. Surfers swallow ten times more sea water than sea swimmers, and scientists wanted to find out if that made them more vulnerable to bacteria that pollute seawater, and whether those bacteria are resistant to an antibiotic.

Scientists compared faecal samples from surfers and non-surfers to assess whether the surfers’ guts contained E. coli bacteria that were able to grow in the presence of cefotaxime, a commonly used and clinically important antibiotic. Cefotaxime has previously been prescribed to kill off these bacteria, but some have acquired genes that enable them to survive this treatment.

The Beach Bums study, published today in the journal Environment International, found that 13 of 143 (9%) of surfers were colonised by these resistant bacteria, compared to just four of 130 (3%) of non-surfers swabbed. That meant that the bacteria would continue to grow even if treated with cefotaxime.

Dr Anne Leonard, of the University of Exeter Medical School, who led the research, said: “Antimicrobial resistance has been globally recognised as one of the greatest health challenges of our time, and there is now an increasing focus on how resistance can be spread through our natural environments. We urgently need to know more about how humans are exposed to these bacteria and how they colonise our guts. This research is the first of its kind to identify an association between surfing and gut colonisation by antibiotic resistant bacteria.”

Researchers also found that regular surfers were four times as likely to harbour bacteria that contain mobile genes that make bacteria resistant to the antibiotic. This is significant because the genes can be passed between bacteria – potentially spreading the ability to resist antibiotic treatment between bacteria. Recently, the UN Environment Assembly recognised the spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment as one of the world’s greatest emerging environmental concerns.

Despite extensive operations to clean up coastal waters and beaches, bacteria which are potentially harmful to humans still enters the coastal environment through sewage and waste pollution from sources including water run-off from farm crops treated with manure. In the paper, the authors demonstrated the prevalence of cefotaxime-resistant E. coli in UK bathing waters as well as the prevalence of the mobile resistance gene that make bacteria cefotaxime resistant. They estimated that over 2.5 million water sports sessions occurred in England and Wales in 2015 which involved ingestion of E. coli bacteria harbouring these mobile resistance genes. They found that surfers are particularly vulnerable to ingesting the bacteria because they swallow up to ten times more water than sea swimmers.

The antibiotic resistant era

The World Health Organization has warned that we may be entering an era in which antibiotics are no longer effective to kill simple, and previously treatable, bacterial infections. This would mean that infections such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhoea, and food and waterborne diseases could be fatal. It would also mean that it would no longer be possible to use antibiotics to prevent infections in routine medical procedures, such as joint replacements and chemotherapy.

The 2016 O’Neill report commissioned by the UK government estimated that antimicrobial resistant infections could kill one person every three seconds by the year 2050 if current trends continue.

Up to now, solutions on addressing the issue have largely focused on prescribing and use. However, increasing priority is being placed on the role of the environment in spreading the problem in addition to transmission within hospitals, between people and via food.

Science and Policy Officer David Smith said: “While the Beach Bums study highlights an emerging threat to surfers and bodyboarders in the UK it should not prevent people from heading to our coasts. Water quality in the UK has improved vastly in the past 30 years and is some of the cleanest in Europe. Recognising coastal waters as a pathway for antibiotic resistance can allow policy makers to make changes to protect water users and the wider public from the threat of antibiotic resistance. We would always recommend water users check the Safer Seas Service before heading to the sea to avoid any pollution incidents and ensure the best possible experience in the UK’s coastal waters.”

The study was funded by the Natural Environment Research council and the European Regional Development Fund.